When Is It Needed?

Automation is often thought of as a process that requires systems to "talk" to each other. While built-in integrations can facilitate automation, it is by no means a requirement. But before focussing on the technological problem, a good first step is to consider whether automation makes sense.

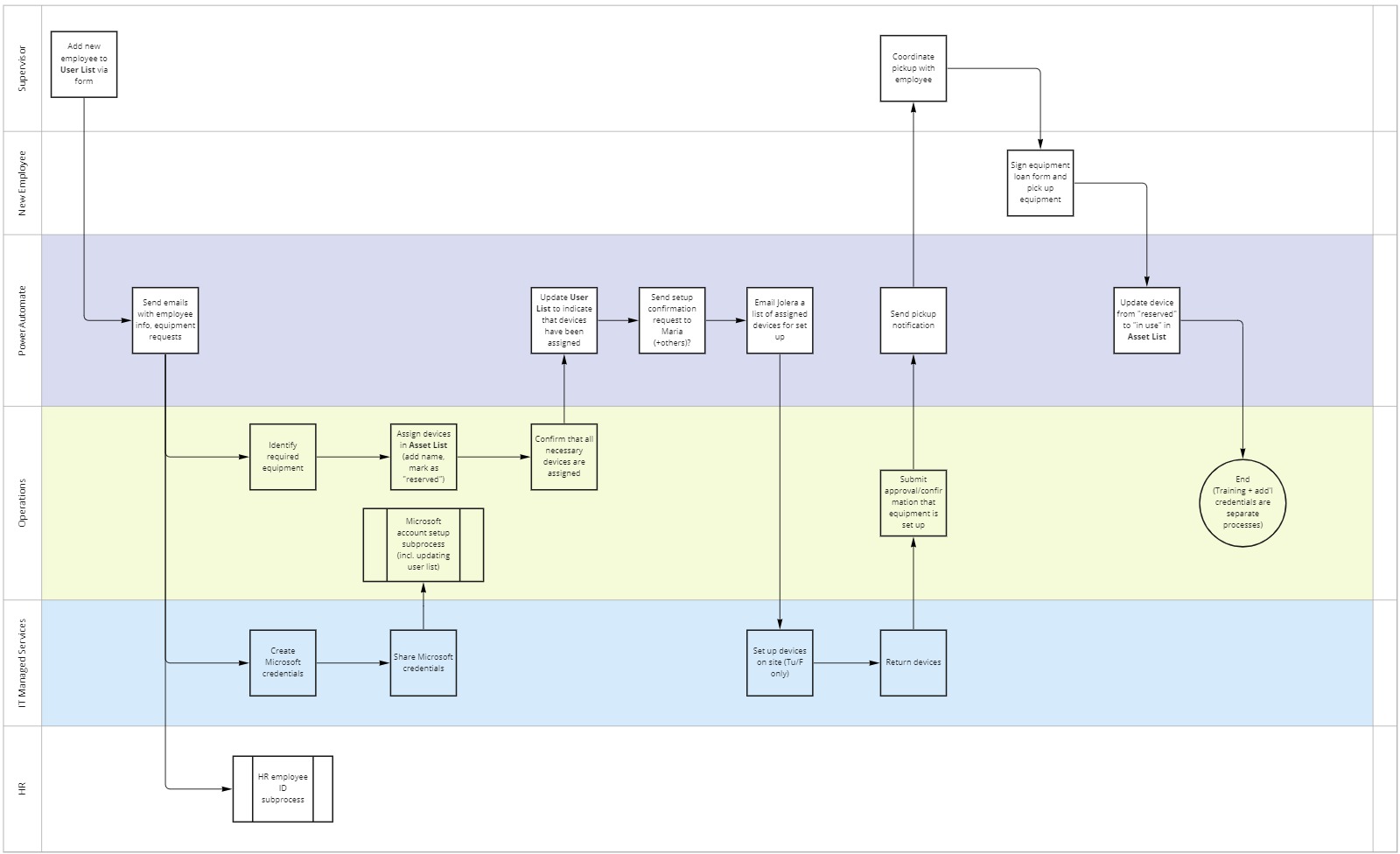

Automation works best for processes that are repetitive, time consuming, or open to human error. Usually, these are tasks that take place on a regular schedule or that are triggered by a prescribed action (such as a form submission or incoming email). Or they can be multi-step tasks that must occur in a particular sequence.

Because automated routines cannot accommodate unexpected variation, implementation usually requires some form of process improvement. Process improvements can have a standardizing influence and may include small things such as optimizing the order in which steps occur, harmonizing practices between staff, and occasionally removing extraneous steps altogether.

Questions that you can ask:

- Are you struggling to complete scheduled or follow-up tasks on a consistent basis?

- Are there tasks that you would do more regularly if they took less time?

- Are staff spending excessive time duplicating electronic information in multiple systems?